The Books Briefing: What We Thought About Classic Books When They Were First Published

Your weekly guide to the best in books

It’s likely you’ve never read, or even heard of, most of the books Atlantic writers have reviewed since the magazine was founded in 1857. Many have gone out of print; others have faded into obscurity in the decades since their original publication, sinking beneath waves of new works and new literary trends. But some have been buoyed into the upper echelons of literature and cemented as classics, must-reads, cultural touchstones.

Among the thousands of book reviews in the archives, some stand out as enduringly strange or significant: an 1886 appraisal of The Scarlet Letter written by Nathaniel Hawthorne’s son, for instance, or the 1967 reflection on reading Doctor Zhivago from Joseph Stalin’s daughter, Svetlana Alliluyeva. The contemporaneous reviews of books we now recognize as classics are also striking, preserving critics’ unmediated impressions of notable works before they came pre-marked with esteem and consequence.

The reception of such books in our archives is mixed: Atlantic contributors recognized Great Expectations as a “masterpiece” but found To Kill a Mockingbird “undemanding.” And a reviewer wrote that On the Road, now widely beloved and considered a defining work of its artistically rich era, “disappoints.”

Each week in the Books Briefing, we thread together Atlantic stories on books that share similar ideas, and ask you for recommendations of what our list left out.

Check out past issues here. Know other book lovers who might like this guide? Forward them this email.

What We’re Reading

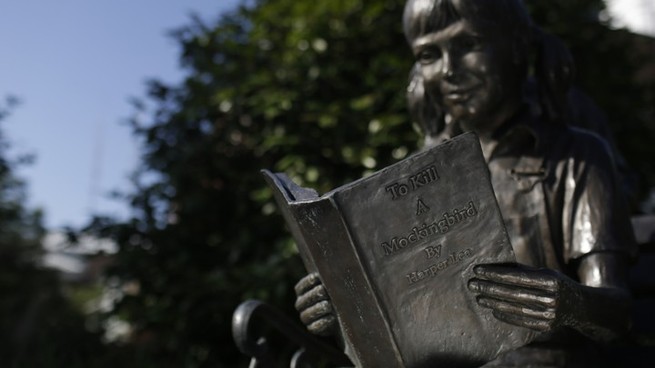

To Kill a Mockingbird is “pleasant, undemanding reading” (1960)

“It is frankly and completely impossible, being told in the first person by a six-year-old girl with the prose style of a well-educated adult. Miss Lee has, to be sure, made an attempt to confine the information in the text to what Scout would actually know, but it is no more than a casual gesture toward plausibility.”

+ 2016: “The elements of To Kill a Mockingbird … have been varnished by time”

📚 GO SET A WATCHMAN, by Harper Lee

“Lolita blazes … with a perversity of a most original kind” (1958)

“The novel’s scandal-tinted history and its subject—the affair between a middle-aged sexual pervert and a twelve-year-old girl—inevitably conjure up expectations of pornography. But there is not a single obscene term in Lolita, and aficionados of erotica are likely to find it a dud.”

+ 2005: Lolita “keeps the promise of genius”

+ 2018: “Lolita will always be both ravishing and shocking”

📚 THE ANNOTATED LOLITA, edited by Alfred Appel Jr.

📚 THE REAL LOLITA: THE KIDNAPPING OF SALLY HORNER AND THE NOVEL THAT SCANDALIZED THE WORLD, by Sarah Weinman

On the Road “is most readable” but “disappoints” (1957)

“Mr. Kerouac makes considerable play with [Dean’s] disorderly childhood, his hitch in the reform school, and his rootlessness, but his activities seem less a search for stability than a determined pursuit of euphoria. Dope, liquor, girls, jazz, and fast cars, in that order, are Dean’s ladder to nirvana, and so much time is spent on them that it is hard to keep track of any larger pattern behind all the scuttling about.”

+ 1998: “In the aftermath of the publication of On the Road … ‘everything exploded’” for Kerouac

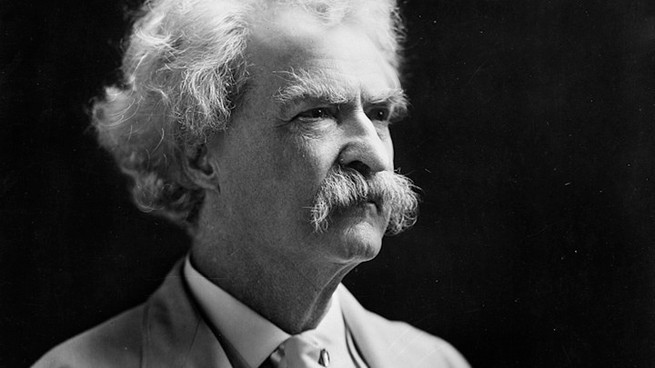

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer is “a wonderful study of the boy-mind” (1876)

“The local material and the incidents with which his career is worked up are excellent, and throughout there is scrupulous regard for the boy’s point of view in reference to his surroundings and himself, which shows how rapidly Mr. Clemens has grown as an artist.”

Great Expectations “is a masterpiece” (1861)

“In none of his other works does [Charles Dickens] evince a shrewder insight into real life, and a clearer perception and knowledge of what is called the world. The book is, indeed, an artistic creation, and not a mere succession of humorous and pathetic scenes.”

+ 1877: The story of Great Expectations “haunted Dickens’s imagination”

You Recommend

Last week, we asked you to recommend stories of self-reinvention, resolve, and renewal. Connie Kennedy, of Iowa, put forward The Glass Castle by Jeannette Walls, in which, “coming from a childhood replete with example after example of living on the border of a disaster with parents stuck in fantasy, the author—through sheer determination—creates a completely different life for herself.” Another reader, Katelynne, suggested How to Build a Girl by Caitlin Moran, describing the book as “a masterpiece of sophomoric insight” in which “a teenage girl decides to re-invent herself solely on her will and talent.”

What’s a book you’ve read twice and changed your mind about? Tweet at us with #TheAtlanticBooksBriefing, or fill out the form here.

This week’s newsletter is written by Annika Neklason. The book she’s reading on her commute right now is The Color of Law, by Richard Rothstein.

Comments, questions, typos? Email aneklason@theatlantic.com.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.